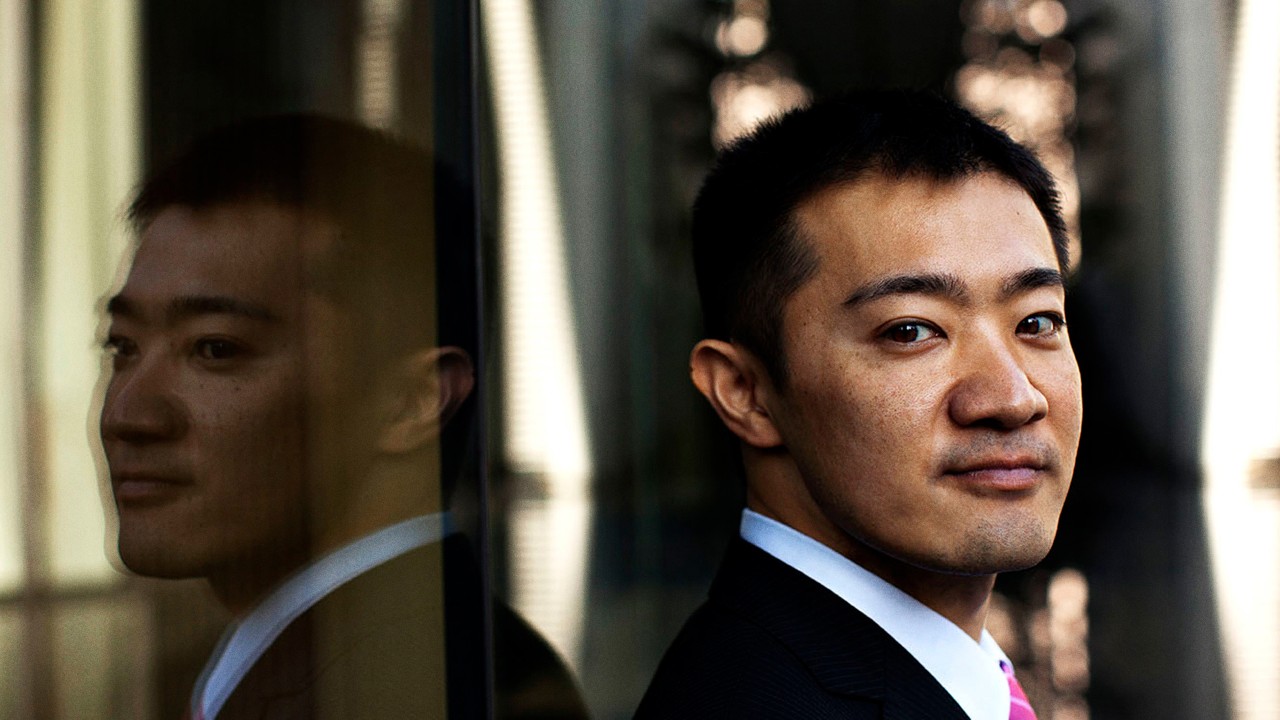

Xue Bing

A Pressure in My Heart

Ambitious goals and hard work – that’s what 46-year-old Xue Bing’s life revolved around. As cofounder of a rapidly growing teambuilding firm, he was realizing the high achiever’s dream. His job was to motivate and excite other people – but he lost his own spark to severe depression.

Xue Bing

China

46 years old. Married.

Employment

Xue is a partner in a team-building company that he cofounded. Over the last 20 years it has grown rapidly, attracting major investors. Now it is poised to expand further.

diagnosis

During 2016, Xue began to feel increasingly bleak. For a long time, he thought he was exhausted by his hectic working life and just needed rest. Yet his misery escalated into intense thoughts of suicide, among other things. In the spring of 2017, he was diagnosed with major depressive disorder.

Xue Bing recalls how focused he used to be when he led a teambuilding session. One of the activities he often did with a group of clients was rock climbing – an exercise that demanded his full attention. It was his responsibility to ensure that the safety harnesses and helmets were properly adjusted, so that no one got injured. He constantly needed to pick up and act on the needs of every single participant. It was as if his mind managed to expand under pressure: “Just a few seconds of delay and I’d react too slowly – but I was quick!”

Xue challenged his clients to conquer fear, to trust themselves and to push their limits. And their feedback was enthusiastic. One success catapulted him to the next, and two decades passed in a whirl of long workdays, airports and hotel rooms. For years, he gave everything he had to achieve his escalating ambitions. And during the whole time, his cognitive skills served him faithfully. Logical, constructive, precise and extremely responsive – those are the words he uses to describe himself. Time flew – and he could match its speed.

I’m so tired

When did he start losing altitude? It was gradual, during the course of 2016. He used to immerse himself in his work with clients. Used to enjoy the laughter and camaraderie of his coworkers at the end of a working day. Now he looked at the clock in the middle of a session and wished it would be over soon. Now he withdrew to his hotel room instead of sharing a meal with his colleagues. And he began to doubt – to doubt whether he was good enough. Whether he was still equal to the task.

“I longed to feel the self-confidence and passion I inspired in others. But I didn’t feel anything at all”

Xue Bing

He explained his state to himself as simple tiredness. Yet it was a strange tiredness; contact with the outside world began to seem meaningless. And in his inner world, a disturbing thought began to intrude. To soothe himself, he insisted on absolute calm in his surroundings. He called in sick. He walled himself off at home and grew increasingly silent. And when his young daughter would sing or dance, his sudden fury made her scared of him. His wife attempted to reach him, but he rejected her too. In the end he stopped speaking to her completely, and she and their little girl moved in with family.

Now he was alone.

He’d withdrawn from his surroundings as far as he was able. And yet he couldn’t withdraw far enough. For the frightening thought grew stronger and stronger. “I felt a pressure in my heart,” Xue says, and so intense was this pressure, it almost prevented him from breathing. An inner voice kept proposing the same solution: You’re so tired. There’s nothing for you to hold onto. Go to the climbing rock and this time, climb it without helmet or harness. Climb to the top. And then jump.

There’s help

Xue Bing’s wife had moved out, but she hadn’t given up on her husband. One day she succeeded in persuading him to have dinner at a barbecue restaurant. And there, at the restaurant, he spoke for the first time about everything he’d kept hidden, and how he couldn’t understand why he was in such agony. But she had a hunch. One of her colleagues had committed suicide – and she had suffered from depression. So she insisted that Xue see a doctor. And the doctor listened to his account of sleepless nights and self-reproach, of the fear of failure and his dangerous inner voice. Xue still remembers the doctor’s conclusion. “You have a severe case of major depressive disorder,” he said. And: “There’s help for you.”

When Xue noticed the very first sign of recovery, it felt so convincing that he dared to trust it. “I felt my heart releasing the pressure,” he says. Since then, he’s seen steady progress. His wife and child have moved back home, and he enjoys their company. He’s returned to work with reduced hours, and takes part in the business’ day-to-day operations.

The price of openness

But he’s not the same as before. That’s why he no longer takes on clients, even though he’d like to. “How could I?” he wonders. He’s had trouble remembering and managing complex situations, and those things are critical in a job as team builder. When Xue looks back, he has his own explanation for why things went so wrong. The gap between the demands he placed on himself and what was humanly possible just became too great, and he feels there must be many others who are experiencing the same thing. “The Chinese economy is developing so fast, I think more and more people suffer from depression,” he says. He also thinks that many of them suffer – as he did – in silence, not knowing what’s wrong.

They’re the people he wants to help. Normally, someone with a diagnosis of depression will do anything to hide it. The price of openness is far too intimidating. And much is at stake for Xue too. Both he and his company are held in great respect, and he asks himself what people will think when they hear his story. “Will they judge me and think that I’m controlled by my emotions? Or will they still trust me to make sound decisions?” That’s a question he doesn’t know the answer to. But it’s been his calling to elicit people’s best, he says, and now he wants to do the same for those who suffer as he did. That is why he wants to be open about his medical history.

“Families need to understand,” he says. “Depressed people can’t help themselves. They need help – professional help.”