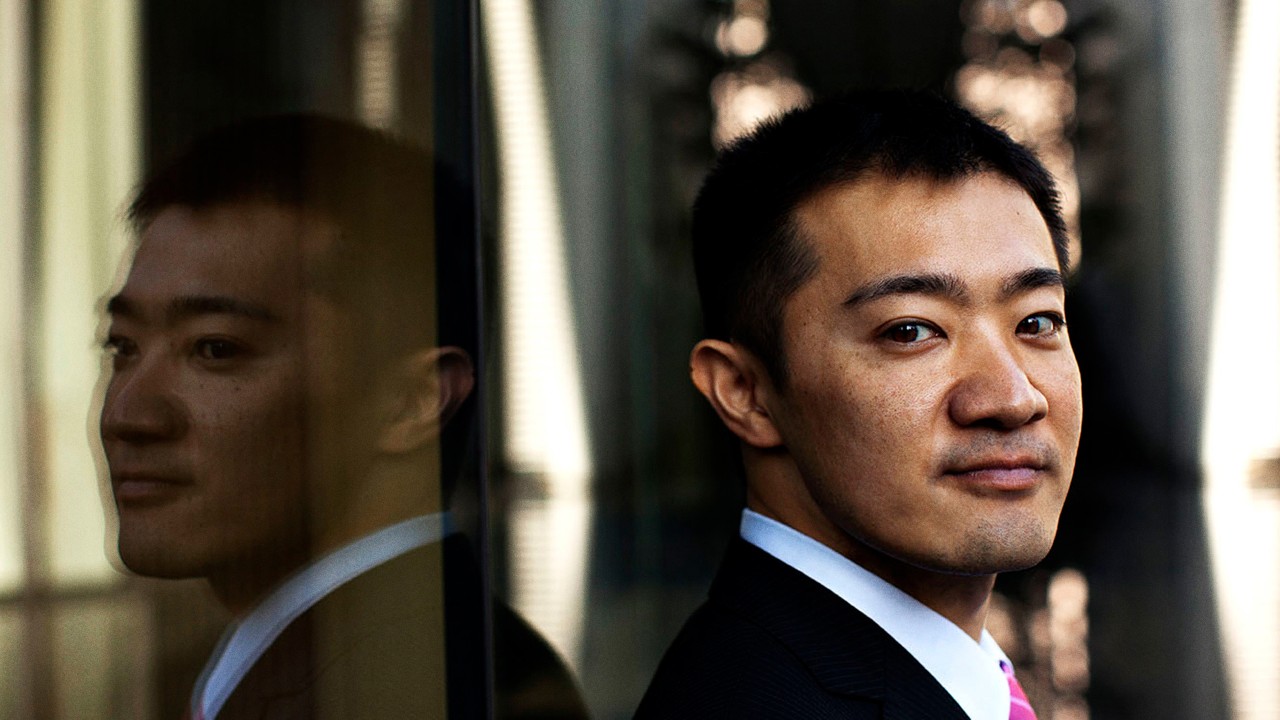

Gary Chanco

Why do you keep looking around, Gary?

Ever since he was young, Gary Chanco has been able to hear a malevolent voice that speaks to him. Gary’s mind is a painful place to be – and often, the outer world feels just as threatening to him as his inner one. Yet he has found some places of refuge.

Gary Chanco

USA

59 years old.

occupation

Menial jobs until 1995, after which he began receiving a disability pension.

Diagnosis

Schizophrenia with various co-morbidities, including bipolardisorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, diabetes and hypertension.

Family

Gary’s parents and older brother are deceased. His contact with the rest of his family is very sporadic.

marital status

In a relationship, no children.

caregivers

Gary receives assistance from the local mental health centre and from Volunteers of America, a charitable organization that provides help to the mentally ill. Since 1979, he’s also received a great deal of support from the local Unitarian Universalist Church.

Gary Chanco turns on the hot water. He enjoys taking long showers, especially if he feels a panic attack approaching. Suddenly he hears a voice speaking. Is it a stranger’s? Is it part of himself ?

He knows the voice intimately. It has spoken to him since he was a teenager, and now, at the age of 59, he hears it a couple of times a week. On this November morning, it suggests to him, in its usual conversational tone, that he turn the hot water all the way up so that he will scald himself.

A conservative family in an archconservative Florida city: that’s where Gary grew up. His father was the pharmacist in the local hospital and Gary’s parents kept a certain precarious health condition of his father’s well hidden from the surrounding world. Already in kindergarten, Gary felt he was different. “I would wonder: Why are the kids looking at me funny? I suffered from insomnia problems even then, and could never take a nap with the other kids on the mat.”

A few years later, Gary was the chubby boy in class who loved to watch cartoons on television; a stuffed Huckleberry Hound lay in his room. The exterior world was an unsafe place. Why do you keep looking around, Gary? his classmates would ask. That question had two answers, and he was unable to say either one. The first was that he was afraid of being beaten up by the bigger boys. As an adult, Gary still remembers distinctly the words that one bully shouted at him after giving him a thrashing. The second answer was that he was becoming more and more convinced that someone might stab him from behind with a knife. Anybody. He had to look over his shoulder to check who might be lying in wait. And then check again.

I kept it to myself

The first time the voice spoke to Gary, he was 12 or 13 and out biking. As he remembers it, the voice simply ordered him to bike home. After that, its message was always the same, albeit with endless variations. Gary? the voice said. Why don’t you slash your wrists. Shoot yourself in the head. Jump in front of the train.

Gary had always been a quiet boy, and now, as he sought to accustom himself to the voice, he grew almost mute. “I kept it to myself. I figured maybe everybody hears voices. Or maybe this was a voice from beyond the grave.” At home, there might go several days during which he didn’t say anything other than Pass the mashed potatoes, please. In school, he sat in the back row to make himself invisible. And at night he lay awake while everyone else slept. But it became harder and harder to slip under everyone’s radar. To wheel around to avoid the raised knife. To not know when the voice might speak to him again. In the end, Gary forced himself to ask his parents if he could talk with a psychiatrist. But they resisted. Couldn’t he just think of something else? Gary’s father was especially opposed. If it became known that his son was mentally ill, what good did it do for him to conceal his own illness? For Gary’s father suffered from severe chronic depression, which was being treated with electroshock therapy at another hospital than his own.

Nonetheless, Gary ended up with a psychiatrist, who decided to admit him to a psychiatric ward. Gary remained there for five months and celebrated his 16th birthday with some fellow patients as guests. Each of them got a slice of chocolate birthday cake with chocolate frosting.

A prison for patients

Gary has been in and out of mental hospitals ever since; he himself guesses that he’s had 15 hospitalizations. Until his early forties, he managed to support himself with jobs as a dishwasher and janitor; one treasured memory is the few good years he worked as an assistant in a computer lab. “I was able to hide my illness and was never fired from any job. But usually I’d quit after a year or so. It’s hard to do a good job and fight mental illness at the same time.”

Many Americans suffering from severe mental illness find themselves receiving less than adequate care at some point. Particularly in Florida, which ranks 49th among the 50 states in terms of per capita mental health funding. For Gary, it happened in the middle of the first decade of the 2000s, when after several tumultuous years he landed in an assisted-living facility. The place was situated in a dangerous neighbourhood, and he had to share a room with three other men who also suffered from severe mental illness. Each of them watched the others suspiciously; were his roommates planning to steal his sparse belongings?

In the mornings, Gary sometimes woke to a cockroach scurrying up his arm. The management skimped on residents’ food, and his diabetes grew worse. He still remembers the woman who distributed medicine throwing his pills on the floor. Why’d you drop them? she smirked as he gathered them up.

For Gary, rescue arrived in the form of his outpatient case manager at the local mental health centre. She managed to wangle him a place on the waiting list for a better-funded, more secure residential facility. Almost two years later, it was finally his turn, and Gary was able to leave the place he remembers as “a prison for patients.” After his numerous moves over the years, he says that most of his belongings have been scattered. One of the few things he took with him that time was Huckleberry Hound. And a photo album.

“I kept it to myself. I figured maybe everybody hears voices. Or maybe this is a voice from beyond the grave?”

Gary Chanco

A few weeks one summer

These days, Gary’s life has achieved a fragile peace, though his health has been compromised by decades of mental and physical illness. He manages to look after his small apartment, and he is surrounded by a network of caregivers – including a life coach who comes every Wednesday from the mental health centre to see him.

A new person entered Gary’s life in 2012. Not a treatment provider, and not a new acquaintance either. But a boyfriend. He’s the first boyfriend that Gary’s ever had, and the relationship has helped draw him out of his shell. “I’ve been lonely for most of my life. Looking back, I feel sad about my failure to commit to a relationship.”

Here’s what Gary’s parents often said to him: Don’t look at boys like that. Here’s what the bully from school shouted after beating him up: That’s for being a faggot. And here’s what he keeps hidden in his photo album: two pictures of himself with another boy. They’re teenagers. He seldom looks at these pictures, for they need to be protected from yellowing. But he thinks of the boy in the picture often. “We can call him Bob, even though that’s not his name. We were close for a few weeks one summer, and I think it’s the deepest connection I ever had in my life. We hugged and he wanted to take it further. I was afraid to. And I’ve regretted it ever since.”

A stable point

Every Sunday morning, Gary can be found in a low white building on a residential street close to the ocean. Here, he joins a community that he first discovered 35 years ago, a community that has functioned ever since as a stable point in an otherwise turbulent life. “These people are largely what keep me going. They all accept me for who I am.”

He’s referring to the Unitarian Universalist Church, which has its roots in liberal Christianity. On Sundays, Gary operates the sound system during the service. And on every fourth Thursday, a good 250 people show up at the church’s soup kitchen for a free meal. Gary oversees a team of up to eight volunteers, who serve food and drinks to the hungry crowd. Many of the guests are homeless, many mentally ill.

He could well have been one of the people who stand in the food line, Gary says. “Without the love and support of the church, I’d probably be homeless.” He smiles a little. “I would be the one receiving food, rather than the one handing it out.”